Hastingleigh.com A genealogy website/One Place Study contact e-mail

World War II - and Hastingleigh

The six years between 1939 and 1945 remain very vivid in the minds of those living in Hastingleigh at the time. Kent felt the full impact of the War and Hastingleigh was in the direct path of doodlebugs (flying bombs) and bomber aircraft attacking London to the North West

Doodlebugs also known at V1 (Vengeance 1) flying bombs were first fired from Europe to target England in June 1943. An average 190 of these bombs was launched each day. Most of them were aimed at London, but many ran out of fuel early and crashed onto Kent.

Or were attacked by our allied aircraft, before they could reach London.

They were very noisy and people could hear them flying through the air. If the noise of the

engine cut out, that was a sign that it was falling to earth and would explode. So everybody

would rush to hide themselves in bunkers, under tables, or in cellars.They were 26 feet long, with a 17 foot wingspan and carried 1870lbs of explosive. About 7000 of these bombs landed in England, causing a huge amount of damage and many civilian casualties.

Later on, the V2 Rocket was used. It was much bigger at 46 feet long by 5 feet wide, and carried 2000lbs of explosive. It was 5 times faster than the speed of sound, and because of its speed, most people had little warning that the rocket was heading their way. Some 3000 V2 rockets were launched towards England, and these rockets terrified everyone, because they were not targeting any specific place, they just randomly crashed and exploded, often in towns and villages.

Over 7000 civilian and military people were killed by the exploding V2 rockets.

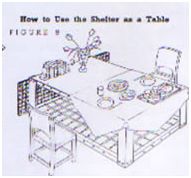

At Bishop Cottages they had outside Morrison Shelters. A steel topped table with metal mesh sides. Half a million were issued free, in kit form, from 1941 onwards. They were much more portable than the more famous Anderson type shelters. Tom Young recycled his when the family moved to New

Barn Farm and it became a work bench/table in a farm shed.

Morrison Shelters were usually inside the home. Mrs E Blaskett recalls that when she lived at Bishop Cottages, they were watching a Doodlebug come over when the engine cut, and her father ordered all the children into the Morrison Shelter, when he did a head count, one child was missing, his eldest son was still sat on the outside toilet, and Tom Young flew down the garden, grabbed his son and raced back to the shelter just in time. That Bomb exploded just two fields away from them.

The Womens Land Army was a very important feature of the War in the countryside where they were expected to replace the men called up on active service. Women could earn 6d (2½ p) per hour and men 7s 10d. They were also expected to work 52 hours a week in the summer and 48 hours in the winter, and work every day of the year. Farmers recall the order to plough up their farmland as the Kent War Agricultural Committee wanted to ensure 30,000 extra acres under production before harvest of 1940. Household gardens and parks were dug up to plant crops of vegetables and fruits. Not just to feed humans but also farm animals. (Click here for Land Army memories)

In 1944 Tom Young who was part of the Kent Agricultural committee was allocated to Naccolt Farm in Brook. During the summer of 1946 his farm labour workforce was supplemented by 4-5 German Prisoners of War. They would be dropped off each morning by lorry, to work the fields. At lunchtime they came to the farm house for lunch which they had to eat OUTSIDE. They were not allowed in the house. They worked unguarded, and were collected by Lorry each evening and returned to their POW camp. In September 1947 Tom Young and family went in to partnership with Bob Shearer of Sellinge and they bought New Barn Farm, Hastingleigh. Bob & Tom worked New Barn until Bob's death, when his share of the farm passed to his wife Mrs Shearer. Tom Young would drive every morning from New Barn to deliver fresh milk to Mrs Shearer who lived at Sellindge. Tom's sons became the labourers at New Barn. There were several POW camps near Ashford which may have supplied casual labour to the farms in and around Hastingleigh:Brissendean Green Camp,

Hothfield Common Camp,

Stanhope Camp

and Woodchurch Camp, Henghurst House.

Trucks would deliver the German POWs early in the morning, my grandmother would take their lunch and tea urns out to the prisoners, but never allowed them near her children or her house.

Jam Making on Florence Empire stoves on trestle tables in the Old Mission Room in Tamley Lane, must have been quite an undertaking. One cwt (hundred weight.) of plums had to make 2 cwt of jam and each grain of sugar was accounted for and all was inspected. The preserving pan took 24lb of material at once. Jam making for the families in Britain was not possible as not enough sugar was available on rations. The Jams that were made in Kent villages were shipped all over the world to supply the troops. Most villages had some form of jam production when the fruit was ready for harvesting.

The Home Guard was manned by volunteers who were not in the Forces and until 1940 they were called the Local Defence Volunteers. The men of the village who were not called up were automatically placed in the Home Guard. Two or three times a week they each took it in turns to guard the reservoir, the most important and vulnerable spot around Hastingleigh for miles. They operated in pairs each night. One man slept whilst the other patrolled. Others were involved in Air Raid Protection. There were only a couple of telephones in the village by this time.The telephone link with the village was at Tappenden's Shop and at the home of Mr Langford, the Dispatch Rider (on motorbike). There were six men chosen for special duties, which they called Hush Hush. These men hid out in unlikely places such as the old ice house near Bodsham school in Evington Park and the cellars of the house itself when it was feared that Germans might have landed and infiltrated, these men were to sneek away for weeks or months in their hide outs and their task was to disrupt the German invading army as much as possible. In the end none of them or their hideouts were needed.

....Mr [Tom] Young was a Special Constable and checked the blackout every night to see that no chinks of light could be seen. As bomber aircraft would fly over to England and if they saw a light on anywhere, they would drop their bombs on it.

All the road signs were taken down, in case the enemy soldiers parachuted in to Kent, they would soon be very lost and hopefully easier to spot and capture. Even now, very few road signs have been put back up, and most of the country lanes in the village are without road names and signs. It is still very easy to get lost in the Kent country lanes if you are not familiar with them.

An amusing tale was recalled by Claude Cooper. A parachutist landed in a field near Crabtree Farm and a naval man who was in the village, rushed out to embrace him. Then it was realised by Mr [Ted] Clarke "That's no Englishman, look at his boots!" The army was called rapidly, to remove the German from Hastingleigh. Mrs Cooper was often up fire watching all night. As well as doodle bugs, bomber aircraft would drop different kinds of bombs and some were called incendiary, these were designed to spread a great deal of fire rather than have a big explosion, and this could destroy crops, haystacks, barns and buildings. Other bombs were dropped silently by parachute and there were other types designed to crash through rooves and cause large explosions.A happy story is told about Fred Prebble who was about 55 at the time. He found a machine gun belt in a hedge and was calmly carrying it home. Luckily it was spotted by someone who realised its danger and Mr Prebble lived on until he was 86. [a machine gun belt was a strip of many bullets which was fed through the machine gun so it could fire rapidly. Each bullet contained explosives.]

The principal fear at the end of the war (1944) was the Doodlebugs. These bombs emitted a flame and on landing, the explosion caused such a vibration as to break locks and windows. This happened twice in a fortnight to Tappenden's shop. One Doodlebug caused the two tin barns at Vigo Farm to catch fire. The fire brigade was called from Wye and took water from the pond to put the fires out. These bombs caused the large craters that we find near Lyddendane, South Hill and Boundary Cottage. A land mine landed in a tree near Lyddendane and hung there with its parachute entangled.

An American Fortress Bomber crashed in the field on the hill above Court Lodge Farm having caught its wing in an oak tree by the chalk pit. [B17 Flying Fortress aircraft were 74 feet long, with a wingspan of 103 feet. There were thousands of them flying out of the UK to bomb targets in occupied Europe. This one was from the US AirForce and returning from a Bombing Mission. ]

USAF B17 Flying Fortress

Mention has been made in the other article of the posts erected to prevent the enemy gliders landing.

Anti-glider poles were a feature of the English and French countryside. Every field that was large enough to possibly be used as a Glider landing strip, had a few telegraph pole sized tree trunks jammed in to the earth.

These would show up on enemy aerial photographs and hopefully deter the enemy from trying to invade by air. The beaches were also fenced off and some were mined to prevent an invasion by sea.

The evacuees arrived and the school children grew more things in their vegetable gardens. These evacuated children had come from London by train, because it was too dangerous to live in certain parts of London. Mainly around the docks where supply ships and troop ships were constantly being loaded with weapons and supplies to be shipped around the world. Some of the children will already have lost their homes due to doodlebug explosions and other bombing raids. As the war went on, Kent became just as dangerous a place to be, and several families with young children were evacuated from Kent to safer parts of England. Sometimes their mothers went with them, but usually the children were sent on their own, because their mothers had vital work to do on the farms and protecting the towns and villages.

A first aid post was ably manned by some of the ladies of the Parish, they didn't just deal with injuries from bombs and explosions, but also any minor injuries and illnesses that needed treating as everyone had to take care of themselves and be as fit and healthy as they could be to help with the war effort. There wasn't a National Health Service at this time, and hospitals were overflowing with wounded servicemen and women and casualties of the bombings. Most Doctors and Nurses were working flat out taking care of the thousands of extra patients with serious medical conditions.(Click) A Letter from the Council stating that everyone who could take in evacuee children, must do so. This was sent out in August of 1939 - a matter of weeks before Britain declared war on the Axis nations. They knew that if war started then London would be the number one target of bombers and was also the most populated city in the country. Most evacuees were children sent to the countryside from London, where they may have already lost their homes due to bombing or were living in an area likely to be bombed. There were also many European refugees who has escaped from the countries that had been invaded by the German forces, and also there were captured Prisoners of War in POW camps.

Canterbury suffered most of all towns in Kent from damage due to incendiary bombs. Peter Schooling, then a grammar school pupil at Simon Langton, cycled to school one morning in May 1942 to find his school and much of Canterbury flattened.

Everyone was required to carry an Identity Card with the senior male in the family as No.1, his wife as No.2 and so on. Each card had a unique reference number which identified the area and town you came from, then your personal number. These ID numbers after the war became people's NHS numbers so they could get free healthcare when the National Health Service was set up in 1948. So anyone alive today who was born before or during the war still has their War ID card number in use today. These numbers were also used when ration books were handed out.

What a relief it must have been for the villagers when food and clothing rationing eventually stopped. The Ministry of Food issued ration books to everyone and where they obtained their rations from was specified. Most people in the village used Tappenden's shop and bakery.

Fortunately, village people did better than their counterparts in the towns as they kept the odd chicken or cow and had vegetable and fruit patches. Can we imagine now living on 2oz tea, 2oz butter, 2oz cheese, sugar and meat and bacon all being rationed and quite rare to get hold of. 2oz is about 56grams [or a quarter of a tea-cup] a week! If you were a fighting soldier you did get a better allowance of food rations than if you were a civilian.Because sugar was really hard to get, items like sweets, cakes, puddings etc were hardly ever made. Fruit wasn't rationed, nor were potatos, or cereals, fish, rice or pasta. However most meat was rationed, so country people caught rabbits, and game birds to supplement their meat diet. Material, readymade clothes and shoes were all rationed. So people mended what could be mended and if children outgrew their clothes or shoes, they were always passed on to a smaller child.

A half cwt [about 25 kilos] of coal was allowed per week. The villagers could collect scrap wood branches to burn instead. With wages at £2 a week on the farms, some people were very resourceful providing what was needed locally. One local person made ladders buying larch poles and fitting the chestnut rungs. Another made rakes from Ash tree branches.

Paper was in short supply, and Newspapers cut down to usually one or two pieces of paper covering all the essential news. However they were not allowed to mention the names of towns or villages that had suffered from bombings. So they would say ' a coastal town' or ' a rural village', and might give one other clue like the name of an inhabitant. This can make it tricky to identify newspaper stories with actual locations even today, and it was just the same in war time, confusing any enemy spies and hopefully not giving too much information to the enemy.

so many bombs and rockets fell in the woods and fields around Kent, that it was impossible to find them all and make them safe. Many are still buried where they fell, and while it should be safe for tractors to plough the top surfaces of fields today, it would not be safe to dig any deeper without being very careful indeed.

WW1 - memories

There was also rationing in the First World War, about which there are fewer recollections published, but one of the oldest residents in the Parish recalls four days on and 4 days off in the trenches, sleeping in the mud and how his school mate with whom he planted the school chestnut tree, was killed there. (The flying bombers of those years were the Zeps [Zeppelins] and Mrs [Emily] Young said that brother [Nelson] Haywards dog could hear them when they came over Dover and would start whining. The Germans and the British had giant airships. These were used for aerial photography of the ground troops at first and later used for dropping bombs on specific enemy targets.

French Canadians were camped in the Cow Leese Meadow during the 1914-18 war and had to bring the horses to the village pond to drink; coming in to the shallow end, one soldier went in head first when his horse put its head down to drink! [Cow Lees Meadow is the field at the first cross roads to the West of the village High Street, opposite corner to Folly Town Farm.]

Mr Marsh recalls

" Two giant airships stationed at Chilham when I was a child, were HMA Silver Queen and HMA Delta. The crew in their white uniforms would wave as they flew low over quiet Hastingleigh, just clearing a large Ash tree by Vigo farm."